Ed Glassman: Adapting, Connecting and Moving

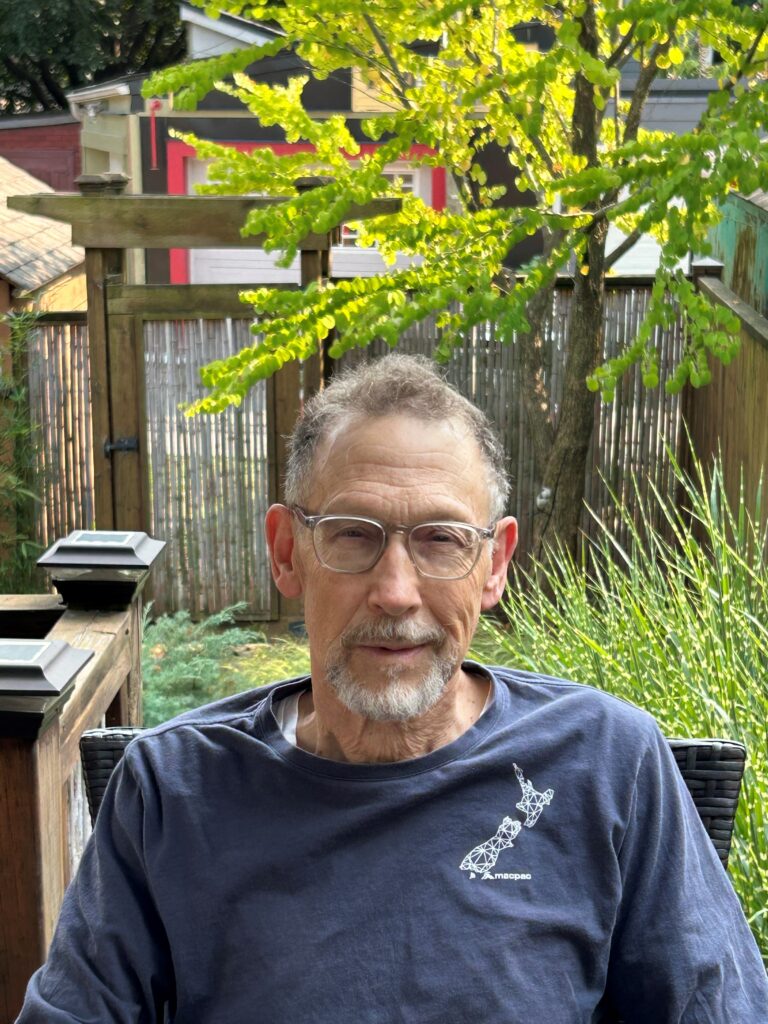

October 10, 2024, is World Mental Health Day in Canada. We spoke to retired psychologist Dr. Ed Glassman about his experiences of living with cone dystrophy and to get some tips on how to manage your mental wellbeing.

“Adapt, adapt, adapt — that’s been my mantra,” says Dr. Ed Glassman.

It’s the mantra he’s been using since he received the diagnosis in which he learned he has cone dystrophy, a rare disease, over 25 years ago. Dr. Glassman, who is now retired was then working at the North York General Hospital in their mental health program, where he worked for 25 years before going on to teach at the York University graduate psychology program.

When he was trying to figure out what was wrong, he says he tried to focus on getting the diagnosis — finding specialists, setting up and going to appointments, doing research.

“If I allowed myself to think about it, it would be a sense of panic.”

When he got his diagnosis, he took comfort in knowing that, although he was losing his central vision, he wasn’t going fully blind. Knowing the deterioration would be very slow also helped.

But he was still worried — about what it would mean for him, and how it would impact his wife. They both had to adapt. Dr. Glassman used to be the driver in the family, and that changed.

His work also helped him in adapting. They were generous in giving him time off to consult with experts when he was trying to get his diagnosis, then in providing him with accessibility aids for his computer.

He turned for help wherever he could find it, eventually connecting to Fighting Blindness Canada, which he first learned about when he saw a news story about the upcoming second annual Cycle for Sight fundraising event. He and his wife have participated in at least 10 Cycle for Sight events.

“I thought, I love to cycle, and I’d like to raise money, so it was a really good fit.”

That event got him into long-distance cycling, though he has recently had to give it up, due to his deteriorated vision.

Moving through cycling has been an important part of Dr. Glassman’s life because it is important to move as a part of your overall physical and mental wellbeing.

According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), vision loss has been linked to loneliness, social isolation, and feelings of worry, anxiety, and fear. Depression is common with vision loss. In a recent CDC study, one in four adults with vision loss reported anxiety or depression. And younger adults with vision loss had almost five times the risk of serious anxiety or depression compared to older adults.

“Your capacity to cope with vision loss is going to be better if you have a supportive environment,” says Dr. Glassman. “If not, it will make coping so much harder.”

He recommends people connect with others who are going through something similar. “Connect to FBC,” he says.

He also recommends moving. “When you talk about managing issues, it’s always move your body, get out, do exercise,” he says. There are many options for people with vision loss, like tandem bike riding, blind hockey, blind sailing or goalball, to name a few.

It’s also important for immediate family members to get support and look after their wellbeing.

“If you’re someone like me, where it started in middle age, it’s important to keep in mind the stress on your spouse,” he says. For people who are diagnosed much younger, their parents also experience a lot of stress. “You’re suffering and struggling, but the people around you are also suffering and struggling, and it’s important that they do what they need to in order to stay on an even keel.”

It is also important not to get into a contest about who is suffering or struggling more, Dr. Glassman says. The way to do this is try and create a space to express your suffering, and then be open to listening to the struggle of your significant other(s).

One element that may contribute to depression for people with vision loss (and really any acquired or congenital disability) is adapting to increasing dependency. “I really struggle with my increasing dependency on my wife. When that feeling of dependency is not openly acknowledged, the frustration and hit to one’s sense of self worth can fuel depression,” he says.

With a progressive disease, there is also a fear of what the future holds. “I find it is so easy for my thoughts to dwell on just how bad my vision could become and how negatively that will impact myself and my wife. This kind of worry is rocket fuel for anxiety.” Dr. Glassman tries not to let these worries get started. “If I catch the worry early, I can usually re-focus on something positive in the present. But this does take practice.”

Concrete planning is another way to forestall the effects of fear or worry about what is in store.

Finally, family doctors are a great source of provincially covered support, he says. Just talking to them for 10 to 15 minutes could be a great help, as could reaching out to mental health services. “There are affordable options, and if you can access that, don’t hesitate.”

It’s an important part of adapting.

Join the Fight!

Learn how your support is helping to bring a future without blindness into focus! Be the first to learn about the latest breakthroughs in vision research and events in your community by subscribing to our e-newsletter that lands in inboxes the beginning of each month.